Just when you think most everything that could be written about (or by) The Kinks has been published, along comes a wonderful assessment about the band and the city it has always called home.

Ray Davies has penned two magnificent books, shedding large amounts of sunshine into the occasionally murky (and yes, London foggy) nature of the band he fronted as part of the original British Invasion. Several biographies have picked apart the cantankerous relationship between Ray and his brother Dave, detailing how that combustibility delivered one of the most beloved songbooks in modern music.

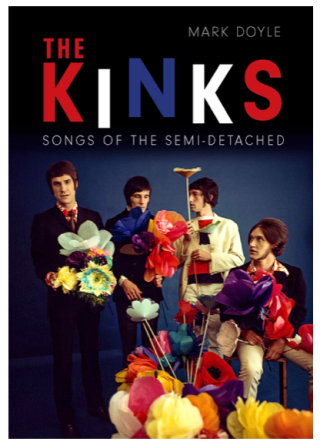

Here, author Mark Doyle brings an academic but far from dry lens to the crucial years of the band, from inception in 1964 to the autobiographical “Muswell Hillbillies” album from 1971. Doyle is professor of history at Middle Tennessee State University. He earlier authored Fighting Like the Devil for the Sake of God: Protestants, Catholics, and the Origins of Violence in Belfast and edited The British Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia, both of which provide a great bedrock on which to examine this quintessential English band.

Doyle points out the band were firmly working class, and as the wrenching changes of the 1960s enveloped London Davies was there to chronicle the changes.

Doyle points out the band were firmly working class, and as the wrenching changes of the 1960s enveloped London Davies was there to chronicle the changes.

Doyle draws trenchant comparisons to the likes of Edmund Burke, Charles Dickens and even the Covent Garden Community Association.

Burke wrote about a certain ‘English wobble’ that described the straight and narrow attitude of the greater European continent, into which the sense of English decency never quite fit. Davies often wrote about that in his insightful sketches of life around London. It was the tug of wanting the idyllic village green and the glory of one’s stately yet humble house, just like the one on either side.

Doyle delves further and elucidates how George Orwell’s 1984 provides caution against the encroachment of authority, as do Davies’ stories about people being displaced from their homes in London neighborhoods like Muswell.

Davies clearly loves and hates the past. He has grappled with that dichotomy for decades, and Doyle does a fabulous job of elucidating the conundrum that is Ray Davies. Even the title of the book works at several levels: the types of houses in which Davies grew up and the observational attitude of Davies, never quite in the moment but acutely aware of what is transpiring.

Look at any photo of Davies and you will undoubtedly see that wry half-smile, he is semi-detached as the shutter snaps.

Recent Comments